Cry the Beloved River

Source : kutlwano

Author : Aron Moreeng

Location : Mabule

Event : interview

Yesterday Kgotlaetsile Kolopo of Mabule village in the Southern District, woke up early and hurried down to nearby Molopo River to water his cattle as usual. Today, yet again, the 51-year old Kolopo is hobbling down the dusty path that leads to the river. His hope is that his cattle will be first in the queue at the watering point he shares with other farmers in the river.

He knows very well that his cattle, as has always been the case, will be waiting anxiously to be provided with water for the day. Although it is a practice he has done since childhood, this time around it is a challenge that is very much different from the past when Molopo River never failed to flood abundantly.

Back then people like Kolopo did not have to wake up early everyday to water their cattle. “There was water everywhere in the river. Our animals could have water with or without our concern,” says the visibly troubled farmer. Sadly, today Molopo River, one of Botswana’s major rivers looks desolate.

Running down the southern part of Mabule village along Botswana’s southern border with South Africa, Molopo River has been the main source of water for the Mabule community for many years. Today, there is no water for either people or livestock. Cattle, goats, donkeys, horses and marine life such as fish and frogs are either desperately thirsty or have disappeared.

It is, therefore, against this background that Kolopo always interrupts his sleep every morning to provide water for his cattle by any means possible. Like on other days, today he thought he was early enough to beat the usually long queue of cattle at the communal well. In fact the river is now dotted with such wells along its course since it ran dry some years back.

Unfortunately for Kolopo, the watering point is already teeming with thirsty animals that moan incessantly as if they went for days without water. This can only mean that the old man was not the earliest after all. Although it has happened before, it saddens him to imagine that he is in for yet another long day at the dry river.

The shortage of water due to the dried up river is a concern not to Kolopo alone but for the rest of Mabule community as well. For many with large herds of cattle, the water from the wells is never enough. On a good day, a single well can only produce about 800 litres of water, which Kolopo says is just enough for about 40 cattle. “We have hundreds of animals to water here every day, and certainly this cannot be enough,” laments the old man.

He says they have to endure digging deeper and deeper from time to time for more water as it gets depleted all the time. What makes the problem worse is the fact that most people in the village cannot afford to drill their ownboreholes to water their animals due to lack of money as well as the dilemma of acquiring land to drill boreholes.

The dry Molopo River does not affect livestock only but the people as well. Those who used to relish fish from the river are now hapless as there is no more marine life in the river. Hunger and thirst is an everyday experience for the people of the tiny village. As such turning the river into a haven for digging deep wells has become a way of life in Mabule.

Interestingly, the situation in Mabule is in sharp contrast to that in the northern parts of the country, where, for instance, Thamalakane and Chobe rivers are regularly flowing, often to the point of bursting their banks.

Recently, authorities in Maun alerted communities who live along the Okavango River against possible floods. In fact, it is common for the Okavango River, to cause untold destruction along its way every time it floods. Who can forget the destruction the Thamalakane River, one of the Okavango River’s offshoots, caused to one of the main bridges in Maun last year?

The most obvious cause of Molopo River’s plight, according to experts and keen observers, is lack of rain. Statistics show that, for some years now Botswana has had less than average rainfall, and this has obviously led to a number of water sources such as the Molopo River drying up.

As it stands, Mabule residents are now pinning their hopes on the Almighty God to bless them with good rains to fill up the river once again. They also hope their South African neighbours would let excess water from Lotlaamoreng and Disaneng dams to flow to their side.

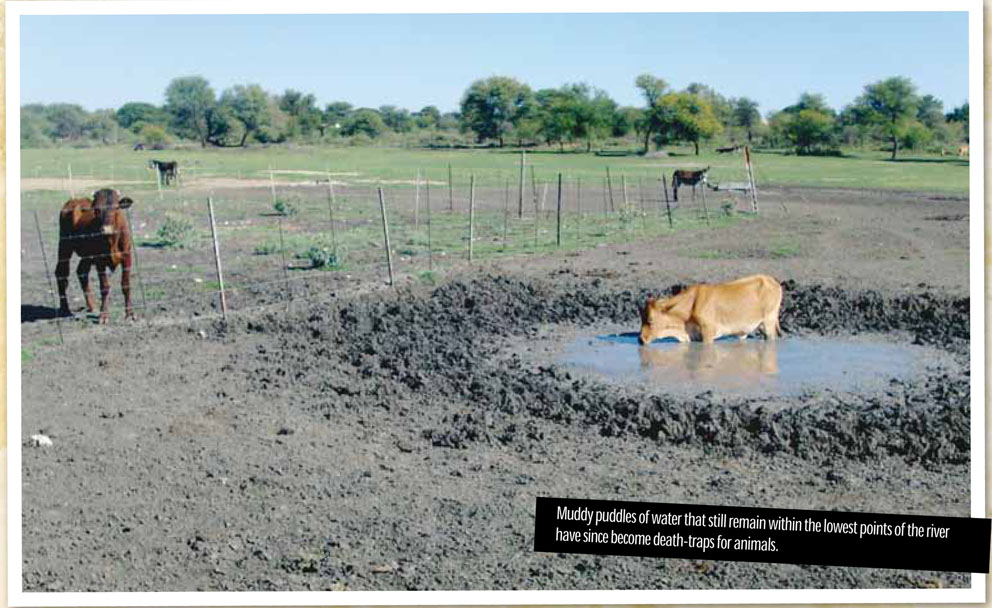

Besides lack of water, there are other problems brought about by the dead river. Muddy puddles of water that still remain within the lowest points of the river have since become death-traps for animals. Cattle get stuck on a daily basis as they scuttle for water. As such meat is in abundance in the village. However, the only downside to this abundance is the fact that the animals are very lean due to the ravages of persistent drought.

Kolopo says their efforts to resuscitate the old borehole in the village have failed. According to the farmer, the borehole used to be the source of potable water for the residents but was abandoned when new ones were drilled.

“We have tried unsuccessfully on several occasions to convince the council to give us the borehole so we could equip it for our livestock,” says Kolopo. He says their intention was to connect long pipes to reach their cattleposts, far from the village. “As I speak, a large number of our cattle (about 30) have strayed into South Africa in search for water, and usually we never see them again,” he laments.

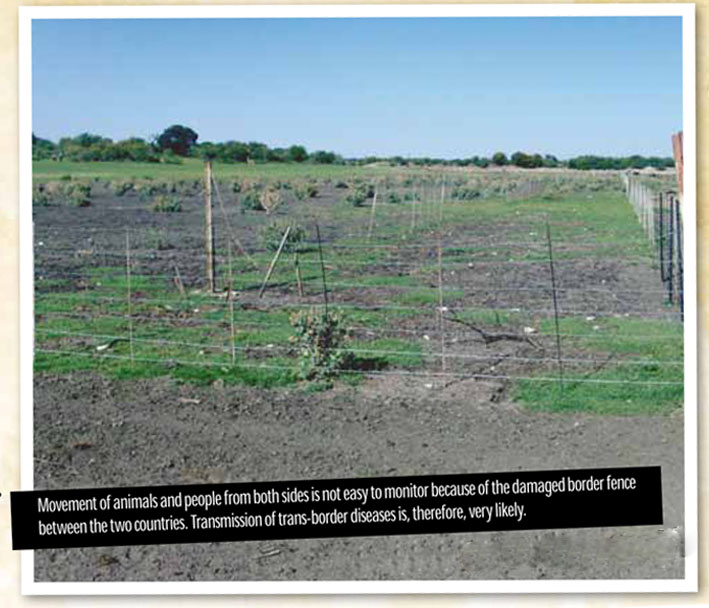

Other problems associated with the drying of the river include border jumping or illegal border crossing. At present, people from either side of the border, cross as they wish because the river does not flow anymore to act as a buffer like before.

In the past, when the river was still a perennial source of water, it forced people to cross at gazetted points. Interestingly, it is not only Molopo River, which basically forms part of the southern border between Botswana and South Africa that is dry since the border fence that used to control movement is also worn out.

Consequently, during the festive season unfettered border crossing by both people and animals was rife. This further compounds the problem of stock-theft and communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS and foot and mouth diseases.

Onkaetse Chwene, another 78-year old resident of Mabule, reveals that some of his cattle are currently in South Africa and he is not sure whether he will get them back. He says driving them back is problematic, particularly the bull which has since become so wild and stubborn. “I think someone with a gun to shoot it down is all I need,” he opines, at the same time lamenting that such was not possible in a foreign country.

Meanwhile, regarding the damaged border fence, principal veterinary officer based in Good Hope, Dr EmmanuelAdom says the South African authorities are responsible for its repair. Dr Adom does not rule out the possibility of trans-border diseases spreading into the country notwithstanding his high regard for South Africa’s firmness in animal disease control.

However, the situation in Mabule is not the only one giving the veterinary officer sleepless nights. Equally, the long stretch of the border from Ramatlabama village has proved to be a trouble spot too. Nonetheless, he says they are working hand in hand with their South African counterparts to address the situation. Although Mabule residents wish for the river to fill up, they are also wary of the floods.

Every time the river is flowing, no less than three people drown in the river, usually while they are enjoying swimming or fishing. In 2010, an old man who was allegedly intoxicated sleepwalked his way into the river and drowned.

Whatever the situation, some youths in the village have remained proud of being associated with Molopo River. Flowing towards the Nossob River in the west, Molopo is one of the unique rivers of the world that flow westwards. In Botswana in particular, rivers naturally flow eastwards. Should the river die, the residents will only remain with a history of a river that was.

The same river that Prince Charles marveled at, back in 1983, when he visited the village on his way to the Commonwealth Development Corporation (CDC) farm that has since been renamed Banyana Farms after the government of Botswana acquired it from the British.

Nonetheless, others have not given up. They say historically there is still hope that the river will spring back to life. For instance, the Thamalakane and Boteti Rivers just recently sprang to life after many years of drying.

Teaser:

On a good day, a single well can only produce about 800 litres of water, which Kolopo says is just enough for about 40cattle. “We have hundreds of animals to water here every day, and certainly this cannot be enough,”