What They Meant... Nope! Implied Maybe

Source : Kutlwano

Author : Baleseng Batlotleng

Location : Gaborone

Event : Social

By contrast, yesteryear’s music had social, political or cultural dimensions regardless of where it was played. Given such, one may be inclined to say that in today’s perspective and as a young listener enjoying traditional song, there is more to derive than what is conveyed beyond the contextual meaning of the time.

The appreciation of Setswana music, poetry and dance is contextual, cultural and to a large extent, personal. It is personal in the sense that like beauty, it is in the ear of the beholder. We dance to the sound of music in personal ways. We carefully choose what we listen to and decide which part of our bodies should respond to the rhythm in play. Observing a group of grown-ups melting the night away with Matshwaro, by a traditional segaba virtuoso, Ratsie Setlhako, it is obvious that they seductively wiggle the lower part of their bodies to drive the point home, an indication of matshwaro that the old man was talking about when he composed his lyrics.

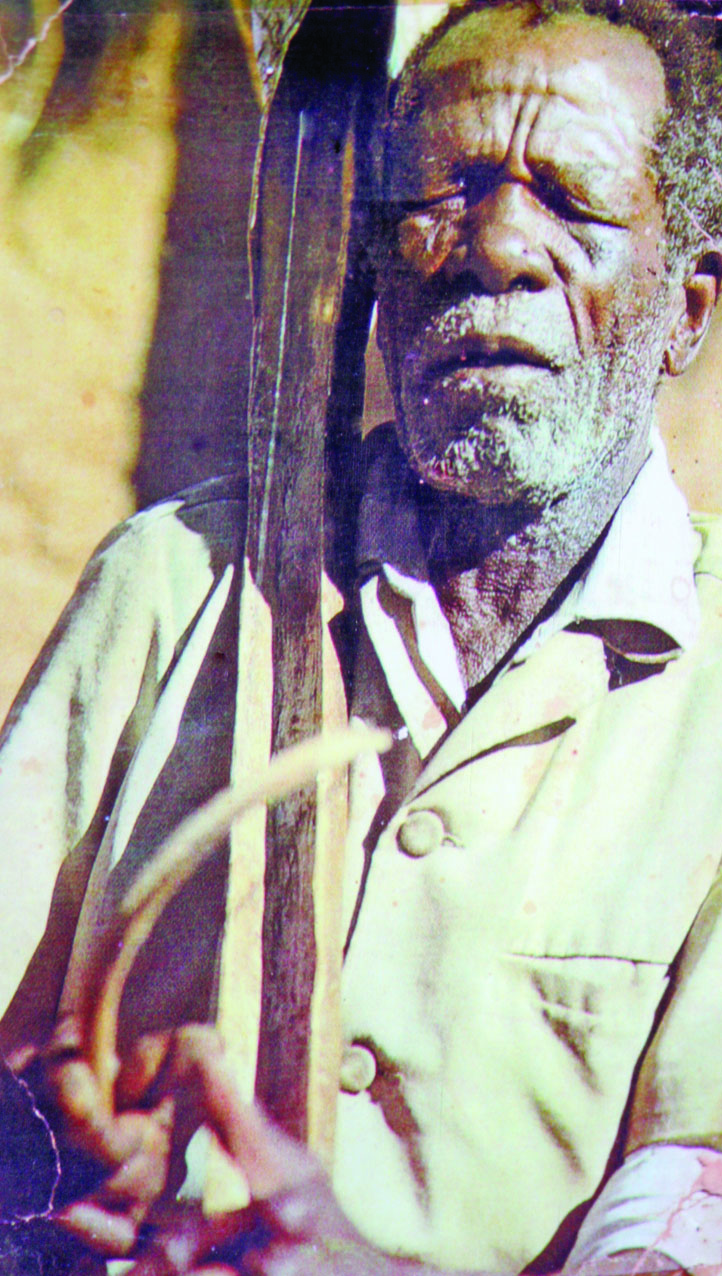

Basically, when Ratsie Setlhako put together many of his pieces, he looked beyond the individual listener in that he wanted to play to the gallery, as they put it. Like many of his contemporaries, his musical pieces wanted to reveal the society of his day and its configurations.Littered with sexual connotations, Mosimanewatsie as he was known by his audience, foretold his society’s social ills ranging from infidelity, moral decadence and casual sex which, according to him, sexual partners were exchanged willy-nilly. Unlike many of his contemporaries, his lyrics carry irony and leave his audience dumbfounded.

“ kgarebe ha o se botlhale, o tlaa dika o ithwele

E se mekgwa ya ga mogatso, oithwele makgoanyana

Lwa bobedi marwalapene…”

Here, Ratsie Setlhako sends a stern warning to a sexually active young woman against her illicit sexual behaviour. She uses strong metaphors to explain the pains of a dishonest pregnancy, “Ba nkitla ka letswele, tlhoko botlhage le dinoka, tlhoko jwa letheka ga bo tswe, ga ke a kgora ke loilwe…”

Ratsie Setlhako embalmed sex and romance in most of his songs, including Banyana ba Mmakau and Marobanyana.

However, never before has a folklore artiste captivated his audience with controversy as the late Letlhakeng-born Speech Madimabe. He captured the moral decay of his society by flavouring his songs with carefully chosen explicit language. His trademark song, sebodu (stench or rot) was basically to tell a story of a society rotting because of illicit affairs. Some say Madimabe was a male chauvinist who believed that a man had to fulfill his sexual obligation to his wife and on the other hand the wife was responsible for all household chores, including child bearing.

Ponatshego Mokane, a praise poet, will be best remembered for chronicling dikgosi notably Tshekedi Khama in a way no one has ever done before. Mokane mastered the trickery of praising his master but yet again using his trick of Setswana language to question some of his decisions. Despite Tshekedi being known as a vindictive leader, Mokane conceals this character but brilliantly explains:

“ le seka la takatakela Tshekedi, Tshekedi ke tau o taa le metsa

Re bone a bolaa motho maloba ga se ka gatwe sepe

Ke leruarua le marapo a thata e a re go jewa ke ngwana a bopame

Ba ga bone ba dikile ba mo leletse….”

Mokane was exaggerating his master’s strength comparing him to a large sea mammal (whale) at a time when Tshekedi was at the height of his career as Bangwato regent. Some viewed Tshekedi as a stern kgosi given his infamous dealings with the Ratshosa brothers in Serowe and the Bakalanga-ba-ka-Nswazwi and many other rival members of his royal family. Another reputable poet who had a fair share of praising his kgosi was Sekokotla Kaboeamodimo. RraKeneilwe, as he was affectionately known, was a tricky orator who could beg from his master in a language only audible to him. In his poem, Kwena, a dedication to Kgosi Seepapitso IV, he pleads:

“…. a ko o rapele morwa Dikgageng, O rapele kgosi e nkatlamele

A nnee kgomo ke ye go e anywa, ka kwa ga Rramonnedi ke kotame hela

Ke eme hela ke sa kganela sepe, kana ha motho a boka o itatswa mabogo

Ka ke itse ha ke boka seharatlhatlha ke boka motho o marapo a thata…”

Here, Kaboeamodimo was telling his kgosi that his praises to him deserved a reward. Along his stanzas he threatens the kgosi that if he does not get his reward he will use a borrowed horse and travel to Morolong to praise Kgosi Besele II of Barolong who is always ready to offer gifts. As they put it, pina ya Setswana ga e na bosekelo and generally has more interpretations to it because of the poetic licence such artistes enjoyed. It is a matter of applying your mind to the music and personally revealing the somewhat hidden message. And as a way of appealing to their audience the folklore artistes used their genius to carefully choose explicit content and avoid spoiling the aesthetic effect of their music with cheap lyrics. ENDS

Teaser:

…it is obvious that they seductively wiggle the lower part of their bodies to drive the point home!