KGWISANGWANA: Maboso VS Bomatlhalela

Source : Kutlwano

Author : Mothusi Soloko

Location : Gaborone

Event : Interview

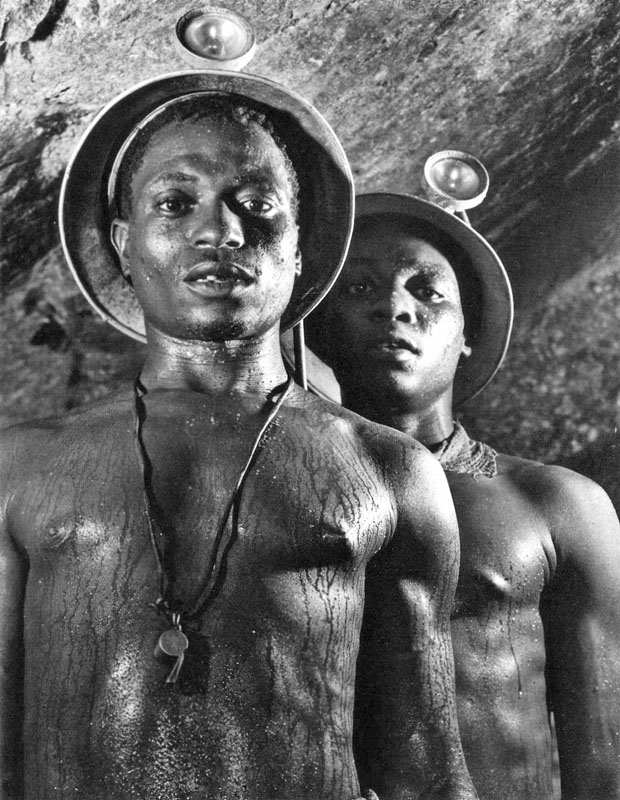

The recent overcrowding of the Gaborone bus rank by former migrant mine labourers bore all the hallmarks of yester-year recruitment centres, save for the absence of Kgwisangwana, a moniker that fit hand in glove with the Greyhound bus that ferried the miners to and from South Africa.

The unprecedented indaba was called by the South African Mine Workers Provident Fund, a trust that aims to mitigate the hardships former miners have had to endure since leaving the multi million rand mines.

Scores of the old men, now in the twilight of their life, even had a hard time trying to put names to faces of former hostel mates who had popularised their title as “Maboso.”

Everything looked like a recurrence of activities at Native Recruitment Centres, which were popular as NRC, an agency that later metamorphosed into The Employment Bureau of Africa (TEBA).The former miners` expedition to Gaborone was driven by nothing else but hope for bringing finality to what had been the darkest period of their lives.

The excursion revived memories of them taking a trip down south, back in the seventies and late eighties, to a foreign land in an endeavour to make monies for the family. When leaving the country, the

The logic behind the naming was simple, maboso were popular for impregnanting their partners everytime they came back home.

So if a partner was on maternity confinement, she had to Kgwisa the infant, literally stop breastfeeding, because pregnancy was on its way, something akin to weaner production on calves. “We were notorious for leaving behind pregnant women hence the bus that transported us comically assumed the name kgwisangwana,” says Modisaotsile Sekai of Mmamkgodi.

However, the Kgwisangwana also had the torture side of it owing to stoneage means of communication. Writing a letter was the only reliable means of connecting, say Molepolole and Klerksdorp, and the letter took months to reach its recipient.

The easiest way to send a letter to the family, if a leboso did not come to kgwisa ngwana, was through a blue or pink envelope, labelled ‘by hand post`, and the addressee would follow below.

Otherwise the “lady of the house” would have to physically wait at the bus stop for the bus to arrive with the hope that her leboso would be on board. Somehow

Kgwisangwana was adored by many especially the young single ladies such that most could distinguish its sound and hooting from other buses from afar. Women often greeted it with ululations.

“As we alighted jealous young men would tease us by calling us maboso. In turn, we would retaliate by calling them bomatlhalela,” recalls Sekai, noting that at times working in the mines was a cool thing.

There were lots of goodies that came with the kgwisangwana luggage.

Perculiar was a bag of oranges, sweets especially pink romantics or liquorice for the children and a dress for the wife or girlfriend plus a suit for the uncle.

Obviously that could be the reason Kgwisangwana was very popular as a conduit of turning lives around.

In fact, in villages such as Molepolole where a good majority of men worked at the mines, it was almost a given that after a few salaries one would build a modern house for his parents.

Statements such as; nna ngwanake o kwa Lejweleputswa o epa gauta ebile o nkagetse haisi, were a common refrain among women who bragged that their children worked across the border.

These statements, however, were uttered with a fair aura of caution because in sad unfortunate cases the son would not come home through Kgwisangwana but a van having been involved in a fatal accident.

Once the rock table collapsed, sadness enveloped the family of the miner because at the minimum he would be involved in an accident that rendered him useless to the mine.

“That is why it was common to hear people saying so and so o wetswe ke tafole,” commented another former miner.

The men talked about the roasted full chicken and the brandy that they used to drink in the bus.

Popular during the recent indaba was an elderly man whom others addressed as “Pitchos man.”

He is said to have been semi-literate at the time, and as a result knew the secrets of all the miners because they crowded in his room begging him to help them write a letter back home.

All these happened during the advent of the notorious Pass Law in South Africa, where black foreigners were restricted to a 90-day stay in South Africa per year, whether on work or social visit.

Sadly though, these miners are credited for contributing immensely to the economic dominance of Johannesburg even though they have nothing really tangible to show except memories of a youthful life punctuated by marks of middle class opulence.

The afro hairstyles, Michael Jackson styled curls, Crocket and Jones shoes matched by Brentwood pants are now a thing of the past as the former miners now potray frail looking body frames on ill-fitting and oversized coats.

Whether they will salvage their dues from their former employers remains a challenge as some documents in the process have been lost.

Some have died while their spouses do not know their makholoskopo [mine identity number] while some have been excluded as the fund covers only those who worked from 1989 to date. Ends

Teaser:

“We were notorious for leaving behind pregnant women hence the bus that transported us comically assumed the name kgwisangwana”